When England’s Laura Bassett kicked the soccer ball into her

own team’s goal last week, England lost its Women’s World Cup semi-final match

to Japan.

It was a mistake. She’d attempted to kick the ball away, of

course, but the ball went left off her foot instead of right and snuck past

England’s goalkeeper. Bassett wept. Her teammates hung their heads. Soccer fans

throughout England were crushed.

Through all this sadness and disappointment, there’s

something for us to learn. As an educator, I think there’s tremendous value in

mistakes of all shapes and sizes. I maintain that every mistake can be viewed

as a positive because it reveals a little bit of the truth.

If we’re solving a problem, a few solid mistakes lay the

path to the solution. This morning I was conscious of the truth-revealing

nature of mistakes as I dropped my two young daughters off for the first day of

their one-week technology camp called “Adventures in Robotics.”

The Debugging

Philosophy

During the camp, which is run by the California-based company

ID Tech and held on the Evanston campus of Northwestern University, I’m hoping

that my girls make hundreds of mistakes, perhaps even thousands, as they learn

how to create computer programs to bring small robots to life.

Part of what they’ll learn is how to debug the instructions

they type into a computer. If the program does not work properly, they’ll have

to figure out why, fix it and try again.

|

| Seymour Papert |

No educator has spoken more persistently and eloquently

about the value of mistakes in learning and adopting a “debugging philosophy”

than mathematician and Massachusetts Institute of Technology professor Seymour

Papert. For decades, the now 87-year-old Papert has argued that schools have

given the word “mistake” a bad name. He explains this in his 1980 book

“Mindstorms” (subtitled “Children, Computers and Powerful Ideas”).

“The ethic of school has rubbed off too well. What we see as

a good program with a small bug, the child sees as ‘wrong,’ ‘bad,’ ‘a mistake.’

School teaches that errors are bad; the last thing one wants to do is to pore

over them, dwell on them, or think about them,” Papert writes.

He continues in his book, “The child is glad to take

advantage of the computer’s ability to erase it all without any trace for

anyone to see. The debugging philosophy suggests an opposite attitude. Errors benefit

us because they lead us to study what happened, to understand what went wrong,

and, through understanding, to fix it. Experience with computer programming

leads children more effectively than any other activity to ‘believe in’ debugging.”

In 1999, I had the good fortune of taking a class with

Papert at MIT while I was attending the Harvard Graduate School of Education.

The class had no tests, no assignments and no textbooks. Instead, led by

Papert’s questions, we spent each class discussing and debating ideas and

talking through how people solve problems. It was marvelous.

“Everyone learns from

mistakes”

My daughters this week will have a bit more structure in

class. Their teacher, whom I met this morning, goes by Dr. Beats (aka Nathan)

and studied robotic engineering at Worcester Polytechnic Institute. He will be

introducing the class to LEGO Mindstorms’ robotic platform to teach them how to

use motors, sensors and computer programs to create robots.

|

| ID Tech's Dr. Beats |

LEGO Mindstorms was developed through a partnership between

the MIT Media Lab and LEGO. The origins go back to Papert. In the 1960s, Papert

co-developed a programming language called LOGO aimed at improving the way

children think and solve problems. LOGO allowed a small turtle robot to

draw line graphics based on simple computer commands. It encouraged exploration

and experimentation by both the students and teachers. To Papert, this is key.

“Some people who observe the children’s growing tolerance

for their ‘errors’ attribute the change of attitude to the LOGO teachers who

are matter-of-fact and uncritical in the presence of programs the child sees as

‘wrong,’ ” Papert writes. “I think

that there is something more fundamental going on. In the LOGO environment,

children learn that the teacher too is a learner, and that everyone learns from

mistakes.”

A Glimpse of the

Future

In addition to making mistakes and learning from them, I

hope this week my girls have fun and develop confidence in their ability to

solve problems. As a parent, though, I must confess an ulterior motive. If this

experience happens to ignite a spark that leads either or both of them to a

future interest in computer science, that will be just fine.

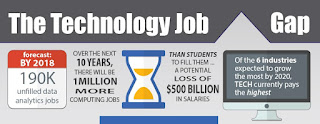

I am keenly aware that as my girls reach college in 10 years

and then begin their job search, computer science jobs will be abundant. In

fact, over the next 10 years, there will be 1 million more computer jobs

than students to fill them. Moreover, of the 6 industries expected to grow the most

by 2020 (just 5 years away), technology pays the highest at an average of $78,730

a year. (See an infographic created by the Computer Science Zone.)

|

| Credit: computersciencezone.org |

The reality is that our schools are not doing enough to

prepare students for these jobs. Today, 9 of 10 high schools in the U.S. don’t

offer computer science classes. In addition, girls continue to not choose

computer science as a major or as a career as well. Of all the computer science

graduates today, only 12% are women.

So, while Laura Bassett’s mistake was on a big stage in front

of millions of viewers, perhaps it also offers a glimmer of the truth. Maybe,

as some soccer analysts have suggested, she was out of position slightly,

allowing her opponent to get past her at a critical moment. She tried to adjust,

made an error and no doubt has learned a valuable (and difficult) lesson.

During this week and well beyond, I can only hope the same

for my daughters.